Last week I posted about my findings while reading from the

Mahabharata, an ancient epic poem written in India that contains key beliefs of

the Hindu culture. I dedicated this week to reading from the Bhagavad-Gita, a sacred scripture taken

from the Mahabharata that is so important to Hinduism that it is often treated

as a free standing text. The poem recounts a conversation between Lord Krishna

(later revealed to be the Supreme Being himself) and a prince named Arjuna who

questions the war he’s fighting against his own cousins. As they stand on the

battlefield with both sides ready for conflict, Lord Krishna (often referred to

simply as “the Lord”) teaches Arjuna his duties as a warrior in the caste

system of India and also instructs him on how to live a righteous life. As

such, this text allows us to have a better understanding of Hindu theology and

the caste system of ancient India.

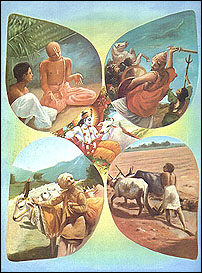

The caste system of ancient India consisted of four classes: (in descending order) the priestly class (Brahmins), the warrior class (Kshatriyas), the merchant and peasant class (Vaishyas), and the labor class (Sudras). The Brahmins interceded between gods and men and therefore were entitled to everything. The Kshatriyas were obligated to protect the people from war and injustice. The Vaishyas were expected to tend cattle and cultivate crops. The Sudras existed only to serve the other three classes. Although the caste system was strictly adhered to, the Bhagavad-Gita celebrated the ascension above class, relating that Lord Krishna himself was born into a family of Vaishyas. Lord Krishna (the Supreme Being) invites all classes to follow him, promising equal rewards if not equal opportunity.

The caste system of ancient India consisted of four classes: (in descending order) the priestly class (Brahmins), the warrior class (Kshatriyas), the merchant and peasant class (Vaishyas), and the labor class (Sudras). The Brahmins interceded between gods and men and therefore were entitled to everything. The Kshatriyas were obligated to protect the people from war and injustice. The Vaishyas were expected to tend cattle and cultivate crops. The Sudras existed only to serve the other three classes. Although the caste system was strictly adhered to, the Bhagavad-Gita celebrated the ascension above class, relating that Lord Krishna himself was born into a family of Vaishyas. Lord Krishna (the Supreme Being) invites all classes to follow him, promising equal rewards if not equal opportunity.

"Understand this: no servitor of mine is lost. Even people of low origins, women, vaisyas, nay sudras, go the highest course if they rely on me. So how much more readily holy Brahmins and devoted royal seers! Reduced to this passing world of unhappiness, embrace me! May your thoughts be toward me, your love toward me, your sacrifice toward me, your homage toward me, having thus yoked yourself to me as your highest goal (107)."

|

| India's caste system |

Even so, the extent of your religious worship depended on your class. The Brahmins performed the rites and rituals for themselves and others, being completely versed in the scriptures (the Vedas). The Kshatriyas offered sacrifices and the Vaishyas were permitted to participate in select rituals, but the Sudras were not. The Sudras could not study the scriptures nor observe any rituals nor even hear the sacred chants! Thus, your class determined even your path to salvation. In the Bhagavad-Gita, Lord Krishna explains to Arjuna his religious duties as a warrior, commanding him to go onward to war and not turn back.

"Or suppose you will not engage in this lawful war: then you

give up your Law and honor, and incur guilt. Creatures will tell of your

undying shame, and for one who has been honored dishonor is worse than death.

The warriors will think that you shrank from the battle out of fear, and those

who once esteemed you highly will hold you of little account. Your ill-wishers

will spread many unspeakable tales about you, condemning your skill – and what

is more miserable than that?

Either you are killed and will then attain to heaven, or you

triumph and will enjoy the earth. Therefore rise up, resolved up battle!

Holding alike happiness and unhappiness, gain and loss, victory and defeat,

yoke yourself to battle, and so do not incur evil (77)."

|

| Lord Krishna and Arjuna rushing into battle |

As in Shuan's post on ancient Chinese culture, honor was deeply tied to righteousness and morality. A warrior's honor was to fight for his country, no matter the cost. Each member of society holds a specific role that they must fulfill to be redeemed. This ties into the idea presented by Tanner about how ancient forms of government based themselves heavily in "God-established" hierarchy. No one challenges the authority of the king when there exists a cultural belief placing him on level with God himself. The caste system of India was so deeply entwined with their religious beliefs that it existed for centuries despite the injustice of such a system. Sacred texts like the Bhagavad-Gita coupled with oral tradition conserved these beliefs for perhaps over a thousand years.

"But he who… shows me his perfect devotion shall beyond a

doubt come to me. No one among humankind does me greater favor than he, nor

shall anyone on earth be more dear to me than he.

He who commits to memory this our colloquy informed by Law,

he will offer up to me a sacrifice of knowledge, so I hold. And he who, filled

with belief and trust, listens to it, will be released and attain to the

blessed worlds of those who have acted right (145)."

Ancient Hindus were willing to memorize this discourse, offering a "sacrifice of knowledge" to attain salvation. In today's society where so many are dependent on the written word, would we be willing to make a similar sacrifice? (if not for salvation's sake, then at least to make the grade! see midterm #2 for this class. haha.) Memorizing scripture may seem like a simple (and perhaps useless) task, but ancient Hindus praised the acquisition of this knowledge above all else. We must ask ourselves why. Perhaps there is more than meets the eye to oral knowledge.

Ancient Hindus were willing to memorize this discourse, offering a "sacrifice of knowledge" to attain salvation. In today's society where so many are dependent on the written word, would we be willing to make a similar sacrifice? (if not for salvation's sake, then at least to make the grade! see midterm #2 for this class. haha.) Memorizing scripture may seem like a simple (and perhaps useless) task, but ancient Hindus praised the acquisition of this knowledge above all else. We must ask ourselves why. Perhaps there is more than meets the eye to oral knowledge.

Jake I love your ending bring in how the Hindus believed that memorizing was needed to get into heaven and that we just so happen to have to memorize King Benjamin's speech. Memorization is a skill that just takes time and the more time you take to memorize thing the easier it become to accomplish it.

ReplyDeleteYa I found the part at the end about memorizing their sacred writings really interesting. It sounds just like seminary! But in all seriousness I think it's a testament to just how orally minded their culture was, because the memorization of their beliefs was so important, even a matter of salvation, rather than just writing it down.

ReplyDelete